Brian’s life behind the bench

Brian Sugiyama has spent the last three decades coaching his kids, his grandkids, other people’s kids, and even other coaches who – much like he does – just want to make the game better

When you spend decades doing something you love, you evolve.

Brian Sugiyama has been behind the bench, in the dressing room and on the ice helping kids and young adults become better hockey players and people for the past 30 years.

The 72-year-old Nanaimo, B.C., resident maybe hasn’t seen it all, but he has seen quite a bit, more than most, and has a good sense of what it takes to be a great hockey coach.

“When I first started doing the coaching development stuff, I thought it was more the technical and science of coaching,” says Sugiyama. “Now, I think it’s more the art of coaching, that you’re working with young men and women, sometimes they just graduated from playing minor hockey themselves, sometimes they’re parents. They all seem to think it’s about the Xs and Os and the practices, where I think it’s really more the psychology of coaching, working on childhood development, how kids get along and that you have developed within your team that bonding and that whole area of respect within your teams, respect for your opponents and others involved in the game, like the officials.”

Sugiyama is a member of Hockey Canada’s Coaching Program Delivery Group. He is district coach coordinator for Vancouver Island and clinic facilitator for Coach 1, Coach 2 and Development 1 programs within the National Coach Certification Program, teaching hundreds of new and experienced coaches each year. He is also a High Performance 1 coach mentor and Development 1 coach field evaluator.

To attain those credentials requires time, dedication, experience, patience and an incredibly strong and thorough knowledge of Canada’s game.

Sugiyama has all of those traits.

His journey began, as so many Canadian hockey stories do, on backyard and outdoor rinks. Sugiyama was born and raised in Edmonton and got his start outside when his father built a backyard rink.

As his love of the game grew, so did his skill and commitment. Sugiyama played competitively with the Maple Leaf Athletic Club through his teenage years. He got his start in coaching when he helped out with his younger brother’s team. And then, in the early 1980s, Sugiyama did what so many dads do – get involved in coaching with his own’s son’s team. He and wife Karen have four children and all of them grew up playing hockey.

“I started coaching local recreational divisions at the younger age groups and then you get into wanting to be better as a coach, and you start taking some courses,” says Sugiyama. “I coached a competitive U11 team and you encounter the good, bad and whatever. I still got a lot from it. I thought I could contribute to not only my kids’ development, but other kids as well.”

Later in life, the family moved to Vancouver, where they still reside. And the Sugiyama name is perhaps just as well known in Nanaimo as it is in Edmonton, given the years of service and dedication to hockey given by Brian and the rest of the family.

TJ Fisher helped coach a U15 co-ed recreational team during the 2023-24 season with Brian, one that included one of Sugiyama’s granddaughters and one of Fisher’s kids.

“It’s so neat to see a grandpa coaching grandkids. You never see that,” says Fisher. “It’s one of those things for people my age, it’s like the life goal where you have to keep on evolving with the next generation. He stays current and is totally relatable. He’s really up on technology to be able to be current to both teach his clinics and to stay current with the kids on the team.”

Erin Wilson has also been inspired by Sugiyama. Wilson and Sugiyama coached together during the 2021-22 season and have known one another for close to three decades.

“As both a parent and coach, I really value Brian's focus on fair play and sportsmanship,” says Wilson. “His encouragement of every player to be a contributing part of the team is so valuable and important for individual character development, self-worth and team play. This focus on fair play and sportsmanship is something I try and replicate and is a strong value and focus I believe in when I am coaching a team.”

Sugiyama has been on the bench of competitive and recreational teams and believes there is a gap that will need to be filled on the rec side. Often, there are plenty of moms and dads who want to help out with competitive teams, but a shortage of coaches who want to pitch in on the recreational side.

His impact hasn’t just been felt by regular Canadian moms and dads, though. In recent years, Sugiyama has facilitated and led courses attended by some well-known retired former NHLers who want to give back and coach.

“This last season, I’ve had people like Andrew Ladd and Brent Seabrook and Duncan Keith take the courses,” says Sugiyama. “They’re coming back and imparting their knowledge back to a hockey academy or a team in their community. They come back supportive of what Hockey Canada is doing with the development of coaching.”

Sugiyama jokes with his course attendees that he’s “getting long in the tooth,” but continues his involvement and will as long as he can. That’s not only good news for kids on the ice, but the men and women who have a chance to learn from Sugiyama.

“It’s special to see that whole family,” says Fisher. “He’s still coaching, his kids are coaching, the grandkids are playing. It’s pretty awesome.”

Embracing a new life through hockey

Bridget Vales had never heard of hockey until she moved from the Philippines to Saskatchewan; now she can’t get enough of Canada’s game

Bridget Vales got her first taste of hockey when she went to her stepbrother’s practice shortly after she moved from the Philippines to White City, Saskatchewan, when she was eight years old, and pretty quickly she was interested in trying it out herself.

That first experience didn’t go as expected.

“It was tough,” Bridget, now 14, says. “It was embarrassing for me [at the beginning] because when I went to the tryouts, I didn’t know how to skate. I cried at the rink because everyone was better than me.”

In the end, she made the team and got better every game. The next season, when she was nine years old, she made the ‘B’ team with the Prairie Storm Minor Hockey Association and worked hard to improve her skating and skills.

“I felt happy with how much I improved in hockey,” she says. “But the transition was difficult.”

Bridget comes by the passion of the game naturally. Her mom, Reynilda Vales, quickly fell in love with hockey after moving to Canada from the Philippines on a work visa as a midwife in April 2015. She couldn’t bring any family members at that time, but after two years, she got her Canadian permanent residency and was able to bring Bridget to Regina in 2018. Her employer at the time introduced her to hockey and the love affair began.

“It was my plan to put Bridget in hockey. I am crazy about hockey. I am loud with my intense cheering … I am crazy at the rink,” Reynilda says. “Being from the Philippines, it’s very warm, but when the kids are playing hockey, I don’t care about the cold.”

Growing up in the Philippines, Bridget focused on school and didn’t play any sports. Since moving to Canada, she has embraced her athletic side and participates in hockey, baseball, lacrosse, badminton, volleyball and track. Hockey, though, is her favourite.

“I love to play games and meet new teammates. My favourite part is skating and hitting,” she says. “Hockey is my favourite sport because it just gives me so much joy and excitement. I just love playing it because it’s such a fun sport.”

Hockey is just one of the ways Bridget came to better understand life in Canada. Not only is she able to meet new people and create friendships, but it has also helped her transition to a new life with a different culture, climate, food, language and school.

“I’m glad Canadians love to play hockey. It’s fun learning about hockey because it’s a fun sport to play and watch,” she says. “I feel accepted because I’m in a sport and hockey has been able to give me a team where you feel like you are a part of something bigger.”

Reynilda has been an influence for Bridget in life – helping her navigate coming to a new city and new country, and setting up a new life.

“It’s easy for me to guide my daughter because I came here first and I encountered the same feedback about our culture,” says Reynilda. “Hockey is a part of our lives now. It keeps us busy, and it helps us to focus on the kids’ well-being. It’s just our day-to-day life now.”

It’s not easy making a major life change and moving to another country, but hockey has been valuable in making things easier. The comments Reynilda gets now, it shows how much Bridget has grown.

“The parents now ask if Bridget grew up here because of the way she skates … she doesn’t look like she just started playing hockey,” says Reynilda. “The progress has been unbelievable. I think it’s because hockey is in her heart. She loves it.”

Reynilda and Bridget have fully embraced the Canadian way of life – from learning to ice fish to hockey – but they also share their culture with others.

“I used to be embarrassed because I was different, but now when people find out I’m Filipino, they are interested in finding out more about me and my culture; they want to know my language,” Bridget says. “That makes me happy to share who I am. Hockey has made me feel like everyone else and I feel at home.”

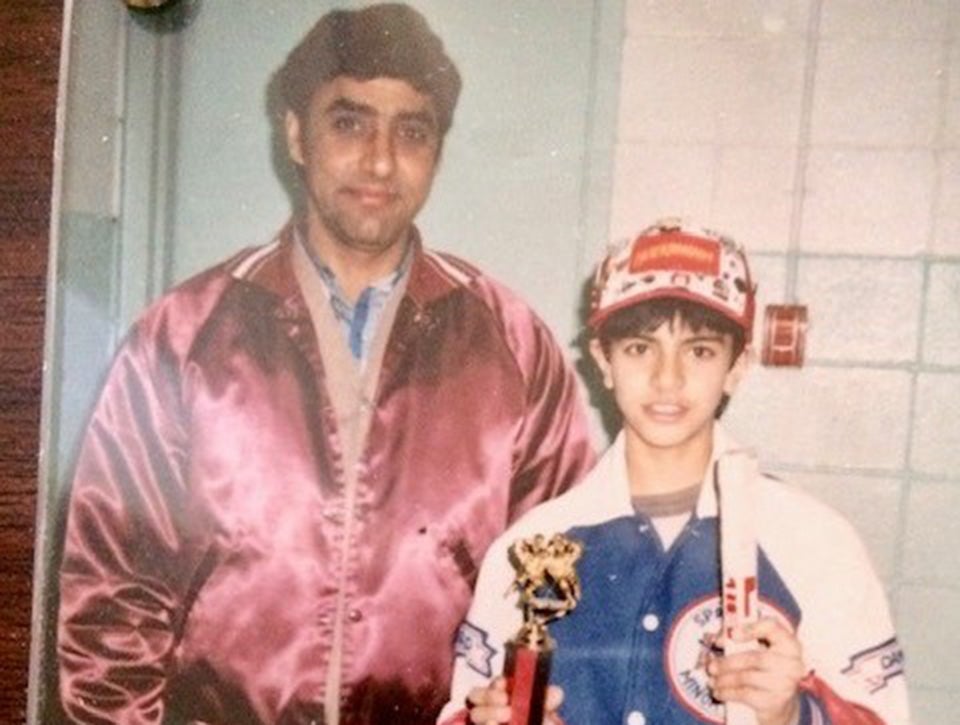

In my own words: Dampy Brar

The coach, mentor, teacher and Willie O’Ree Community Award winner talks about his journey in the game, and the importance of making an impact with the South Asian community

For countless generations, my family lived in Punjab, India. They were honest, hard-working, salt-of-the-earth people. Each generation took over the farming and continued the family traditions and lifestyle.

My dad had a different dream for himself and for his future family. A dream to come to Canada and start a new life with new opportunities. But he never imagined that his Canadian dream would include hockey.

At the age of four, I vividly remember sitting on the front step of our townhouse in Sparwood, B.C., the town I was born in, watching a group of older boys play street hockey. I was instantly intrigued. My dad recognized my interest and bought me a plastic hockey stick with a pink blade, yellow shaft and a black rubber knob, which also came with two plastic pucks. I would play non-stop in our undeveloped basement, shooting into a milk crate.

As the hockey season approached, we were fortunate enough to have older East Indian family friends whose boys played minor hockey in Sparwood, so my dad registered me. There was only one problem – I had never been on skates.

I was incredibly lucky to have a great skating instructor; his name was Tander Sandhu, and he was 11 years old. He says it took me 15 minutes in an old pair of his skates that weren’t even my size to start skating on my own. By the age of eight, I was moved up to play with the older kids after scoring 21 goals in two games.

I kept scoring several goals per game, and then early in the season when I was 11 years old, they implemented a rule that players could only score three goals in a game. Even though I was a playmaker and had a lot of assists, it was pretty well-known that this rule was created because of me. In hindsight, it made me an even better passer; however, my family always wonders if that rule was not implemented how much more attention and exposure would I have received in the hockey community.

I was born in Canada, and simply loved the game. I saw all my teammates and their families in the same manner, but not everyone looked at me as an equal. As a kid, perhaps I was oblivious to the looks and comments. The racism piece really came to light when I was eight. After my third goal, a player on the opposing team, who was from a nearby town, yelled something at me several times while I was taking the face-off against him. A word that started with the letter P, but I couldn’t fully understand what he was saying.

After scoring two more goals, he continued yelling the same word at me over and over again. I can still see what he was wearing, his facial expressions and his anger. I remember feeling scared. I didn’t know what I did wrong, and why he was so upset with me. My teammate told me he was saying something really bad about me. Something about how I look. The taunting continued, but I managed to focus on playing the game and having fun. After finishing the game with 13 goals, he shook my hand and said the word ‘Paki’ yet again, right to my face.

All weekend the incident rolled through my mind. On Monday morning at recess, I asked my older East Indian friend, who also played hockey, what ‘Paki’ meant. He explained that is what they call us in a negative way to make fun of us. It was a name assigned to me because of the colour of my skin.

I got used to hearing it over the years. However, the worst had to be hearing from a parent when I was 15 years old. Just before the game started, with the arena pretty quiet, the father of the opposing goaltender yelled to his son, “Don’t let that f*cking Paki score!” and then looked straight at me with glaring eyes.

Towards the end of that season, we went to a small town in Crowsnest Pass in southern Alberta. It was a Friday night game, and a bunch of teenagers came to cheer on their home team. Instead of watching the game, they stood away from the parents and threw constant racial slurs at me while making inappropriate gestures.

I have never repeated what they said. But if we want to invoke change, we need to be honest with what was said and done. They were saying things like, “Go back home, Paki,” or “Put curry on the puck, it will slide better,” or “Where is the red dot on your forehead?” Any time I took a face-off in front of them, or simply skated past them, they banged their hands on the glass and tried to scare and intimate me.

We won 6-4 that night. My parents were so happy on the car ride home, as they thought I played well; however, I was quiet and numb. When I got home, I had tears in my eyes and asked my parents, “Who cares about the game, did you not see what was happening?” They told me that if I wanted to be an elite player and represent our culture, it was something I would need to endure. My dad then told me some stories of the racism he had gone through on the streets and in the workforce. He wanted to shield me from it, but sadly he could not.

It was then that I really started to envision that one day I would use hockey to earn respect, and then turn around and help other South Asian players and their families.

I had the goal of playing professional hockey, but as we all know, the path to get there is extremely complicated. With immigrant parents, no mentors and no internet, navigating the hockey system was very difficult. Some how, some way, I made it through Junior B to Junior A and to Concordia University College in Edmonton. But I started to doubt that college hockey was the right decision to get me to my goal.

After a few games, an ex-NHL coach turned agent named Bill Laforge Sr. came to watch us play. He was gracious enough to take me under his wing and send me on my way to play pro hockey in the United States.

In my seven-year career, I played five seasons with the Tacoma Sabercats in the West Coast Hockey League (WCHL), where I had two stand-out coaches: three years with John Olver and two with Robert Dirk, who I coach with now at the Okanagan Hockey Academy.

During this time, I really grew not only as a hockey player, but as a person. I learned the importance of community work and giving back. The city showed me a lot of love in return, which overshadowed any discrimination. I won the WCHL championship with the Sabercats in 1999, played in the WCHL All-Star Game and was voted Most Popular Player by the fans in all five of my seasons.

A few other milestones were getting called up to play in the International Hockey League (IHL) with the Las Vegas Thunder, and the following year, signing a two-way contract with the Hamilton Bulldogs of the American Hockey League (AHL), an affiliate of my favourite team, the Edmonton Oilers.

I hung up my skates at the end of the 2002-03 season and knew I had to fulfil my other goal of paying it forward and giving back.

When my now-16-year-old son started playing Timbits, I got involved in assisting, educating, mentoring and coaching our South Asian youth and their families. A few years later, I delved deeper into women’s hockey when my daughter started playing. I was lucky enough to help take this internationally when a women’s team from Leh Ladakh, India, came to Canada for the first time to participate in WickFest, run by Team Canada icon Hayley Wickenheiser.

In the end, my passion for the game comes back to providing support and guidance to South Asian and other ethnic players, connecting the community, highlighting players and parents, and spreading information.

It was through my work with the South Asian community that I was honoured in 2020 to receive the Willie O’Ree Community Award, becoming the first South Asian to win an NHL award, which really drove me to continue to make an impact in the diversity and inclusion component of the game.

Congratulations to Dampy Brar for winning this year's Willie O'Ree Community Hero Award. #NHLAwards MORE ➡️ https://t.co/bZTLKWBhIs pic.twitter.com/vP2sExJJWL

— NHL (@NHL) September 8, 2020

Already, we see a number of NHL teams recognize the contributions of the South Asian community by holding a South Asian Heritage Night. I have had the privilege of being part of the Honour Guard or dropping the puck for the Los Angeles Kings, Winnipeg Jets, Edmonton Oilers and Calgary Flames.

Change is slow, but where there is a will, there is a way. Together we will help improve hockey culture and grow the game we all love. Just like in my hockey journey from the age of four to when I played my last professional game, perseverance and resilience are important factors.

Any road to success will always be under construction.

Pak sets himself up for success

Capping off his final junior hockey season with the Collingwood Blues at the Centennial Cup, Noah Pak has a bright future – on and off the ice

For Collingwood Blues goaltender Noah Pak, playing in the blue paint wasn’t always his first choice. But that changed after he reluctantly strapped on the pads for the first time.

“No one wanted to play goalie in the first game of the year, so my dad volunteered me to do it,” Pak recalls. “I was upset about it, crying as I put on the pads, but I finished the game, I really enjoyed it and I was really glad my dad put me in there.”

It’s a decision that has been fruitful for Pak; the 19-year-old has developed into one of Canada’s top junior A netminders this season. Leading the Ontario Junior Hockey League (OJHL) with 16 wins, along with a sparkling 1.37 goals-against average and .947 save percentage, Pak backstopped the defensively sound Blues to their first-ever OJHL championship banner to qualify for the Centennial Cup.

“It’s been a dream for a lot of our players and our goal at the beginning of the year, to earn an opportunity to compete for a national championship,” Pak says about the National Junior A Championship. “I think we’re prepared and ready for it with the team around us, but also trying to soak it all in and really enjoy the experience at the national stage.”

The Oakville, Ont., native was named OJHL playoff MVP for his stellar play, but as much as he is getting the spotlight for his individual performance, he credits the team around him for pushing him to be the best version of himself, on and off the ice.

“The team and the culture in Collingwood have helped me develop as a player on the ice and as a person off the ice,” Pak says. “With our mindset, there was never a doubt in winning the championship, and with all those individual stats, they’re great, but at the end of the day, we’re all here to win as a team.”

Looking forward to the future

Off the ice, Pak is also preparing himself for what comes next. Committed to Yale University beginning in the fall, Pak understands the importance of keeping his career opportunities open, whether that is on the ice or beyond.

After showcasing his abilities at the Cottage Cup in Collingwood early in the pandemic-shortened 2021-22 season, Pak didn’t hesitate to commit to the Bulldogs when the opportunity arose.

“It was a no-brainer for me, with the program they run in terms of hockey but also on the education side of things, it’s second to none,” Pak says. “I’m looking out for my future once I’m finally done with hockey. It was definitely a surreal time for me and especially for my parents with everything that they’ve done for me, supporting me over the years.”

Although he doesn’t need to declare a major in his first year at Yale, Pak is interested in business and economics, but wants to keep his options open, whether that’s in hockey or school. Regardless of what path he chooses, Pak is thankful for all the support he’s received from his parents over the years.

“I wouldn’t be where I am without my parents,” he says. “They’ve put in countless hours driving and preparing me for games, the amount of money they’ve put into my gear and training, so whenever I kind of look back at my achievements, I’m always grateful.”

Pak’s parents, Dennis and Nancy, have always known their son is capable of looking after himself. Whether it was his commitment to preparation before games, his attitude to overcome challenges or his decision to go the NCAA route, they understood what hockey meant to him and the family’s bond strengthened because of it.

“His determination always stood out to us,” Dennis says. “He’s put in the

work into his training, he was determined to develop close to home in

Collingwood, and we’ve adapted our lifestyle around his hockey schedule. As

long as he’s happy, we’ll support his decisions and be there for him.”

As Pak takes the next step into his hockey career, at the Centennial Cup

this weekend and into a busy summer, he is understanding the importance of

becoming a leader in hockey as well. Growing up in Oakville, he has seen the

diversity of hockey grow and hopes that the trend continues.

As Pak takes the next step into his hockey career, at the Centennial Cup

this weekend and into a busy summer, he is understanding the importance of

becoming a leader in hockey as well. Growing up in Oakville, he has seen the

diversity of hockey grow and hopes that the trend continues.

“Hockey is a sport for everyone,” Pak says, who played AAA with the Oakville Rangers. “I’ve been lucky enough that my parents supported the decisions I made for myself and I think anyone can try to strap on the pads or lace on skates so if I can inspire even just one kid to pursue hockey as a career or even just as a hobby, that’s great because this is the best sport there is.”

While Pak is focused on bringing a national title back to Collingwood, he is also making sure he and his teammates are soaking in the experience together before they move onto the next stage of their lives.

“I look forward to the next chapter of my career and my life, and I want to be able to succeed at the next level as well,” Pak says. “I want to do great things at school and with the Bulldogs program, but I’m living in the moment and we’ll see where hockey takes me.”

Wang looks to the future

Just 14, Aydan Wang is focused on not only his own hockey career, but those of other players of Asian descent who will soon follow in his footsteps

Winnipeg's Aydan Wang might only be 14 years old, but he is already blazing a trail for the next generation of hockey players of Asian descent.

Wang (who turns 15 on June 29) is finishing up his Grade 10 year at St. George's School in Vancouver, where he put up 15 goals and 16 assists in 31 games this season for its U15 prep team. He moved from Winnipeg (where he was a student at St. John's Ravenscourt School) to attend St. George's after his family heard about the academically prestigious school through general word of mouth.

"We did some research and we thought it was a really great fit because it combined both really good academics as well as a CSSHL (Canadian Sport School Hockey League) team," Wang says. "Interestingly enough, one of my close friends from California that I had played with before was also thinking of applying to the school, so we got in touch and decided to both apply. We contacted the head of hockey during this process, who talked to his sources in Winnipeg and he offered me a spot on the team. We didn’t have the best season performance-wise this year, but I felt like there was a lot of growth with our team."

Wang, who plays all three forward positions, was recently back in his home province to compete in the 2022 Hockey Manitoba Male Under-16 Program of Excellence (POE) Top-40 Camp, which was held from May 6-8 at Stride Place in Portage la Prairie. He earned himself a spot at the camp after competing alongside over 100 players at the Hockey Manitoba Male U16 POE Spring Selection Camp, which was held in Niverville in early April.

Even though he is an elite-level hockey player, Wang is laser-focused on his education. He is an exceptional student who has a 4.0 unweighted GPA on a 4.0 scale and a long, family lineage of academic excellence.

His mom Fang, a professor of marketing at the University of Manitoba, and his dad Gang, a financial manager for IG Financial, are both first-generation immigrants who left China in the late 1990s to pursue higher education in North America. Fang was born in the city of Hanzhong in Shanxi province, while Gang is from the city of Guangzhou in Guangdong province. They met while both were students at the University of Minnesota.

"It's a bit stereotypical, but hard work, persistence and a really big strive for excellence are traditional Chinese values that are really exemplified by my parents. They are highly educated, really hard workers and they commit that excellence in both their professional lives and in parenthood," Wang says.

Chinese culture and values have always been a been an integral part of Wang's life. Most of his family still live in China and he has visited many times (although not recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic). He is fluent in Mandarin and when he is at home with his parents, he speaks the language. He is very connected to his Chinese community, both in Winnipeg and Vancouver.

As first-generation Chinese immigrants, Aydan’s parents were not that familiar with hockey. They wanted Aydan to pursue athletics so they encouraged him to play tennis and soccer.

"Aydan first started playing hockey when he was six years old. At that time we knew nothing about hockey but as parents our philosophy was to try our best to let Aydan try as many new things as possible when he was young. Right from the beginning, we saw that Aydan loved being on the ice and no matter how many times he fell down, he would always get back up." Gang Wang recalled.

Not long after Aydan started playing hockey, it was evident to his parents that the game was his love and passion. At 10 years old, he played for Team Manitoba at the prestigious Brick Invitational Hockey Tournament in Edmonton, which features some of the best nine and 10-year-old hockey players from across North America. When Aydan was 11 years old, Gang took him to Toronto to try out for a spring team that was composed of all-Chinese boys.

“We wanted him to get some exposure and know that there were many Asian boys playing hockey, it’s not just you are the only Asian kid playing hockey here. Most of the players on that team played AA or AAA hockey. He really enjoyed the experience and played on the team for another year.” Gang Wang said.

Even though he is still young himself, Wang is aware that there are younger players of Asian descent who are already looking up to him and following his career closely.

"I feel like as a Chinese-Canadian hockey player, every time I make it to the next level, I am showing more kids that they can do what I did,” Wang says. “Just how I look up to those who have made it in college hockey, the Western League and the NHL, kids from younger generations, every time I make it that next step, kids who are younger than me, who are similar, not just Asian players, but kids in general, they can do that as well."

Wang will play for the St. George's School U17 prep team this fall and is looking forward to taking the next step in his young hockey career.

"I feel like I want to just keep developing my skill, making sure I get bigger and stronger,” he says. “The next few years, hitting is going to be huge and I will be playing with older players that are stronger and faster, so I need to get that size up. I need to keep working on my speed, shot [and] stickhandling, just trying improve all facets of my game."

Sunohara embraces her roots

She is a women’s hockey legend, a two-time Olympic gold medallist and a seven-time world champion … but most of all, Vicky Sunohara is proudly Japanese

Once a pair of skates were on her feet, Vicky Sunohara didn’t want to do anything else.

The love of the game came easy for the women’s hockey legend. Her father, David Sunohara, played university hockey with the Ryerson Rams.

“My dad introduced me to the game in our basement and as soon as I got on skates, it’s all I wanted to do,” Sunohara says. “He would make a rink in our backyard and many of my memories with him were of playing hockey. I shared his passion and I loved it.”

She continued to carry that love for the game after David passed away when she was seven years old, but the competition is what she craved.

“I’m very competitive and I wanted to play at the highest level I could play at,” Sunohara says. “My uncle recently shared a story with me. We were playing pond hockey when I was three and I told him that he wasn’t trying hard enough.”

Growing up in Scarborough, Ont., Sunohara played a lot of hockey growing up – whether it was street hockey, pond hockey or structured league play. Scarborough was also where she learned how to develop her game and become the dominant player she was on the biggest stages.

Sunohara’s achievement list is long – two gold and a silver at the Olympics and seven titles at the IIHF Women’s World Championship. She was also an integral part of the leadership group alongside Cassie Campbell-Pascall and Hayley Wickenheiser in the early 2000s.

Feeling on top of the hockey world was a feat Sunohara felt many times, but she also struggled at a young age to understand her heritage and what that meant to her as a person.

Her father was Japanese and her mother is Ukrainian, and growing up she had to deal with name-calling and some bullying.

“There were definitely times when I felt like I wanted to be like everyone else. I had a great experience growing up, but sometimes when I would be called names because of my Asian heritage, I just wanted to be someone else,” she shares. “As I got older, I was mad at myself for wanting that … I am proud of who I am.”

Sunohara credits her mom for keeping her grounded, learning about her heritage and what it meant to come from a long lineage of hard-working people.

“My mom did a great job with me. She told me that I can choose to let them win or try even harder. I wanted to play, and she gave me the motivation for me to realize that potential in myself and it stuck with me,” Sunohara says. “I am so fortunate for the Sunohara family. Now when I think about what they went through … the resilience and perseverance, I am proud to be a Sunohara and share my family’s story.”

Throughout her playing career and now as a coach, Sunohara has had the opportunity to speak to youth about life, hockey and share her story. She was named a recipient of the Sakura Award in 2020 by the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre for exceptional contributions made by individuals in the promotion of Japanese culture and enhancing awareness of Japanese heritage.

“I’ve been asked to do more things later in my career and I’m just doing my little part to give back,” she says. “Sports have always been a huge part of my life and I want to help others and youth get involved. I haven’t always spoken about the situations when I was younger, but I thought it would be positive to share my background and story with others.”

After retiring from the game, Sunohara struggled with what came next. She started at a private women’s hockey academy and really enjoyed the challenge of learning a new skill, as well as working with youth.

“I didn’t see myself as a coach, but I love the competition, learning and helping young female hockey players,” she says.

Sunohara has been the head coach for the University of Toronto women’s hockey team since 2011. In June, she will be behind the bench as an assistant coach with Canada’s National Women’s Under-18 Team at the IIHF U18 Women’s World Championship in Wisconsin.

“I’m coming in and I’m so excited with what that group is doing with the young players. It is so important to have access to resources and information. I can’t wait to share my experience and give my feedback,” Sunohara says. “I can only imagine how excited they are to represent Canada and be successful on the world stage.”

Finding a family in hockey

Pat Lam wasn’t allowed to play hockey growing up, but that hasn’t stopped him from becoming a proud hockey dad and long-serving volunteer with the Nepean Minor Hockey Association

Pat Lam has held almost every role imaginable in minor hockey – head coach and assistant coach at house league and competitive levels, trainer, manager, goalie coach and parent/fan in the stands. Lam even serves as the vice-president of operations with the Nepean Minor Hockey Association (NMHA). With all that experience, it’s hard to believe Lam did not begin playing hockey until later in life.

Lam is a Korean adoptee, raised by a Filipino mother and a Chinese father. According to Lam, his parents did not believe in team sports, only scholastics and music. “They did not view hockey as something that would help me conquer the challenge of life, so therefore I did not play minor hockey at all growing up.”.

Despite not being allowed to play hockey, Lam learned to love the sport through watching the likes of Gretzky, Yzerman, Kurri, Bourque, Lemieux and Roy on his TV every Saturday night during the 1980s. “I loved the energy, speed and just the passion that those around me had for hockey.”

Once Lam got to university, he began teaching himself how to skate on the Rideau Canal and at public skating rinks. Once he became a strong enough skater, he would volunteer to help his neighbour, who was playing Junior B, get some extra shooting practice by “donning some goalie pads and becoming a moving target at our local outdoor rink,” he jokes.

Lam did everything in his power to become a better hockey player while in his late 20s. He attended adult hockey camps and sharpened his skating skills with lessons from figure skating instructors. He has since been playing goalie and defence in local leagues around Ottawa. Even with only having joined the sport as an adult, Lam could feel the positive impact hockey was having on his life and vowed that if he ever had kids, he’d make sure they would have a chance to play if they wanted to.

Fast forward a few years, and now the father of two hockey-playing boys, Lam knew he wanted to help out on the ice as much as possible. Starting in house league, Lam was able to become his eldest son’s first-ever hockey coach. From there, he helped out at a league level as a director of a house league division and experienced his first stint on the NMHA Board of Directors. Once Lam’s youngest son was old enough to play, he was able to coach him at the competitive level for two years. This past year, Lam was elected to his VP role with the NMHA.

Having grown up in a household that didn’t view hockey as a beneficial pastime, Lam has learned just how impactful the game can be and wants to ensure other parents realize the same thing. “Hockey teaches those involved that we are helping to shape the future of kids in hockey and in their lives,” he says. “Making sure that we give them the confidence to compete, to understand the concepts of winning and defeat, how important team and teammates are, and ultimately that any progress and success does not come without effort and setting goals, are critical to the hockey experience. These may only look like hockey goals, but they always translate into real life.”

Lam also emphasizes the importance of getting involved if you can. “It is so important that anyone who has the ability to help shape their hockey association, do everything they can to ensure that the coaches we provide for our children are properly trained and guided with the latest standards and coaching methods, to ensure our players are given every chance to learn all these hockey and life lessons.”

Lam provides a unique perspective on the game. When asked what advice he would give to a family looking to get involved in the sport, he reiterated again the importance of getting involved. “Get involved and volunteer! Hockey is a community. The more you are involved, the more you will appreciate how fun this game is and what a hockey family will mean to you every year.”

Lam also provided some advice for Asian families that may be new to the sport and a little unsure if hockey is suitable for their child. “If your child wants to play hockey – let them. Learn about the sport and know it will provide your child with many social and physical benefits that will help them now and later in life. Socialise and interact with your new hockey family, even if it's not comfortable or normal to you. Yes, there will always be some people who may have difficulty embracing Asian cultures and our communication and personality differences, but the vast majority are great and will accept you and your kids in hockey.”

When asked how the hockey community could work on becoming more inclusive, Lam stated how important representation is. Whether it be community role models like coaches and volunteers, board members to help represent persons of various identities and ethnicities or having representation in the media, it is important that children can see someone that looks like them, “to help show our youth that this game is for all of us.”

He also believes that hockey associations should be targeting Asian communities where hockey may not be a typical consideration of a sport to join. “As a hockey community, we should try to help change the narrative, given hockey’s great impact on one’s social skills and overall development. Social interaction, team and teammates are so important to ensuring that your child becomes a well-rounded adult and helps them prepare for their future away from the protection of a family.”

Having been raised in a family that did not believe in team sports, Pat Lam has clearly established himself as a vital member of the Nepean Minor Hockey Association family and is so grateful and appreciative to be a part of such a great hockey community.

A picture and a puck

A picture hanging on Branden Sison’s wall is a constant reminder of the challenges he has overcome on the way to reaching his dreams

Hanging on the wall of the Sison family home in Edmonton are a picture and a puck; symbols of a dream the family only started sharing a few years ago, when eldest son Branden tried para hockey for the first time.

“It was basically love at first sight because the feeling of skating … [para] hockey skating, allowed me to have more control,” the 21-year-old says.

Sison was born without a fibula in his right leg (fibular hemimelia), resulting in an amputation below the knee. He grew up using a prosthetic and never let it slow him down when playing sports with friends; at least, not intentionally.

“I remember when I was playing, there would be times where my prosthetic leg would malfunction because the foot would be on a pivot access and sometimes the screw would get loose,” Sison says, laughing at the memory. “My foot would be doing 360s while I would be running so that would be a little bit of an embarrassing situation.”

John Sison was working a night shift as a paramedic the first time his son tried para hockey, but said it quickly became the talk of the house. The family even traveled to Leduc, Alta., to watch the 2016 national championship.

“That’s when he first saw national competition and the intensity that was involved,” John recalls. “When he saw that, it became his goal. He has a very narrow vision of trying to achieve what he sets out to achieve.”

Later that same year, at just 16 years old, Sison was invited to Canada’s National Para Hockey Team selection camp. Though he didn’t make the cut, staff saw plenty of potential and asked Sison to keep working with them, which lead to a development camp in Montreal and a series against the United States.

This time, John was in the stands, with his camera at the ready.

“[Branden] more or less managed to get the puck mid-ice and get a breakaway and I was just looking through that lens and I was just hoping that he was able to get that goal,” an emotional John remembers with a smile.

Gesturing to his own face, he adds, “I’m just recalling his face and how it lit up.

“Just for him to experience that moment and know that he managed to achieve what he wanted and for me, that’s all I needed.”

Sison though, says he needs more. Now in his second season with Team Canada, the defenceman is focused on the upcoming IPC World Para Hockey Championship and 2022 Paralympic Winter Games. His goal, and that of the team, he says, is to not only medal at both events, but win them.

“We are putting it all out there for each other and the team because we know that we have a really good chance to win worlds and the Paralympics coming up, so we just want to work really hard for each other because we like to keep each other accountable,” Sison says.

With the COVID-19 pandemic forcing travel restrictions and making camps difficult, most team activities went virtual. They had meetings at least twice a week but needed to train on their own. Despite the challenges, Sison says this is the best he has ever felt physically, and the team is closer than ever.

“We’ve honestly become the most well-knit family that I’ve ever been a part of as a hockey team and it’s kind of crazy because we honestly haven’t seen each other for four, five, six months,” he says.

When thinking about the next few months for his son, John is anxious to see what unfolds. But he is also quick to reflect on everything Branden has already achieved, pointing to the photo as evidence.

“For me, that was the goal that I wanted him to achieve,” John says. “I’m pretty sure he’s going to be successful.”

Though he isn’t focused on personal success, Sison says in the short term, a continued place on the national team is his motivation. But when thinking long term, the young blueliner is more reflective.

“I hope to inspire the next generation of para hockey players, I think that’s what I aim to do the most,” he says. “Regardless of who I am or the identity of my background, I think just playing my heart out, putting in effort and just showing my love for the game is what is going to attract people to it most.”

An unexpected journey

Susana Yuen grew up as part of a busy immigrant family in a hockey-loving home, never dreaming the Canadian game would help her connect with her Chinese heritage

When Susana Yuen tried out for her first hockey team at the age of 18, she didn’t even own shoulder pads. The long-time ringette player had never needed them. But there was a set in her brother’s hockey bag.

“I just kind of went to his bag and just kind of took them, I didn’t even ask him,” Yuen laughs. “And I don’t think he ever noticed!”

Six years later, not only did Yuen have her own shoulder pads, but also her own Team Canada jersey. The diminutive forward from Winnipeg made Canada’s National Women’s Team and represented her country at the inaugural IIHF World Women’s Championship in 1990.

Not only did she help Canada win gold, her 12 points tied her for second among Canadians and put her tied for sixth among all skaters in the tournament.

Despite the excitement and maybe even shock, none of her family was in Ottawa to watch. As Chinese immigrants, Yuen’s parents had a business to run made all the busier by their daughter’s success.

“People in the Chinese community were calling the restaurant to talk to my dad, to say, ‘Oh is that your Sue?’” Yuen recalls. “It was a moment of pride because it was like the whole community was rallying around me and that I was playing.”

Community – and family – has always been a big part of Yuen’s life. Though her parents encouraged her athletic endeavours, they were often too busy to help. Coaches and family friends stepped in to get Yuen where she needed to be.

From that experience came Yuen’s desire to give back to the game as a coach, though she was a little surprised when the opportunity to work with the Chinese national team presented itself, after having met the team only once on a trip to China with her sister-in-law.

“I told them I was involved with the University (of Manitoba) and we sent them an invitation to host them,” Yuen explains. “So they came here for a week and trained … and we set up some exhibition games.

“I really didn’t speak much Chinese then, but as far as the hockey aspect of it, I was able to assist them in that way.”

That was in advance of the 1997 women’s worlds in Kitchener, Ont., where China would finish fourth. It remains one of only two medal-round appearances for the country, which could be a reasonable explanation for why Yuen was then invited to return to China and work with the team full time.

Not one to live with regrets, Yuen decided it was experience she had to try, so she quit her job with the University of Manitoba and sold her truck.

“I think my dad thought I was crazy in a sense, but I told him, ‘Dad, I really want to do this, I really want to help the Chinese team. I really want to see if there’s something I can give to them to elevate their game at that level.’ So he understood why I wanted to do it and he was very supportive; both of my parents (were).”

It was an eye-opening experience for Yuen, who despite her tight family didn’t have any close Chinese friends growing up. While she embraced her family’s culture, she had never experienced it in a sustained and immersive way.

Yuen now sees similarities between her time in China, learning about her own heritage, with the experience of new immigrant families learning about Canadian culture – both experiences done through a love of the game.

“My brother lives in a new area and they don’t have a community centre, so the city comes and floods [a field],” Yuen explains. “And I couldn’t believe how many Chinese kids were out there skating and with their parents … and everybody was blending in … it was so nice to see.”

For more information: |

- <

- >